art21: assume vivid astro focus

avaf fuses drawing, sculpture, video, and performance into carnavalesque installations in which gender, politics, and cultural codes float freely. [art21]

Eli Sudbrack: My Influences

Eli Sudbrack of assume vivid astro focus writes about the people, places and artists that have influences his collaborative multimedia practice. [Frieze]

Lisa John Rogers on Maya Stovall

In Detroit, there are no bodegas, just liquor stores. This is part of why Maya Stovall’s 2014 video series “Liquor Store Theatre” could not have been made anywhere else. [ARTFORUM]

Maya Stovall Talks Exploring Detroit and Other Cities Through Her Work

“I’m not interested in crystalizing or reducing people or places with this work. I’m interested in doing the exact opposite of that.” [Vice]

Chrissie Iles on They Come to Us without a Word

Chrissie Iles, the Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, spoke about pioneering American artist Joan Jonas and the arc of her work on the occasion of the U.S. premiere of Jonas’ commission for the 2015 Venice Biennale, “They Come to Us without a Word.”

To experience the work of Joan Jonas is to enter a labyrinthine imaginative space, whose complex structure of meaning is rooted in an encyclopaedic context encompassing literature, ancient myth, land art and sculptural issues of non-site, dance, theatre, performance, ecosystems and identity. This wide-ranging context describes the condition of seventies Postminimalism out of which Joan emerged, and whose hybridic, process-based character her work played a major role in defining.

Each of Joan’s works encompasses elements of drawing, performance, installation, sculpture, video, sound, objects, and storytelling that all co-exist in relation to each other, spatially, conceptually, and also across time: elements from one work frequently appear in another, sometimes forty years later. The artist Liam Gillick described the central importance of performance in this approach in a recent interview — “[Y]ou are editing in real time…chopping and cutting, breaking and interrupting.” — to which Joan replied: “ [I am] interested in revealing the process…. I am showing you how I make it… [It’s] related to Surrealism and juxtaposing disparate ideas, objects and images.”(i)

The narrative structure of Joan’s work also evokes the literary influence of Magic Realism, in which the real and the present mix fluidly with the fantastical and the surreal. In They Came to Us Without a Word, we are taken through five rooms, each of which has two videos: one addressing the main motif of the room, the other a fragment of a second, ghost narrative that runs through all the spaces, picking up from the previous room and taking us forward into the next.

Layered onto this double narrative is an immersive collage of drawings, objects, sculptural forms and mirrored surfaces in arrangements that resist easy definition. We are not looking at the traces of a performance that has happened, even though a performance has taken place in parallel to this work, and props, objects, and video footage from that performance are present. And we are not looking at a stage set, nor an installation in the conventional sense of the term, even though the structure of each room resembles both. The space is, to use Jens Schröter’s term, transplanar (ii): a multi-planar surface that opens up the optical border between two and three-dimensional space, creating an environment that can become a portal into new readings of narrative, space, identity, and time.

This haptic structure was first formed by Joan in the cybernetic environment that emerged in the 1960s, and it is one of the many reasons why Joan’s work remains so resonant now, in the deep interconnectedness of our all-surrounding digital environment. As Matthew Biro observed of that period, “To view human beings as cybernetic systems was… to recognize their collaborative nature…subject to constant dispersal, transformation, and exchange.”(iii)

It is important to understand this, in order to put into context the central importance of myth, symbols, ancient ritual, and literature in Joan’s work. It has a feminist, cybernetic aspect that underpins her interest in writers and thinkers such as Aby Warburg and his “denkraum” (“space of thinking”), the labyrinthine spaces of Jorge Luis Borges, or the writings of George Kubler, whose book The Shape of Time pointed out that we understand history through its material traces, since temporal expression – talking, dance, song, music, ritual – have not, by their very nature, survived, except in the re-telling. Joan juxtaposes the material and the temporal in ways that profoundly understand this conundrum, and the importance of experience, memory, and what cannot be recorded or recalled, in the construction of meaning.

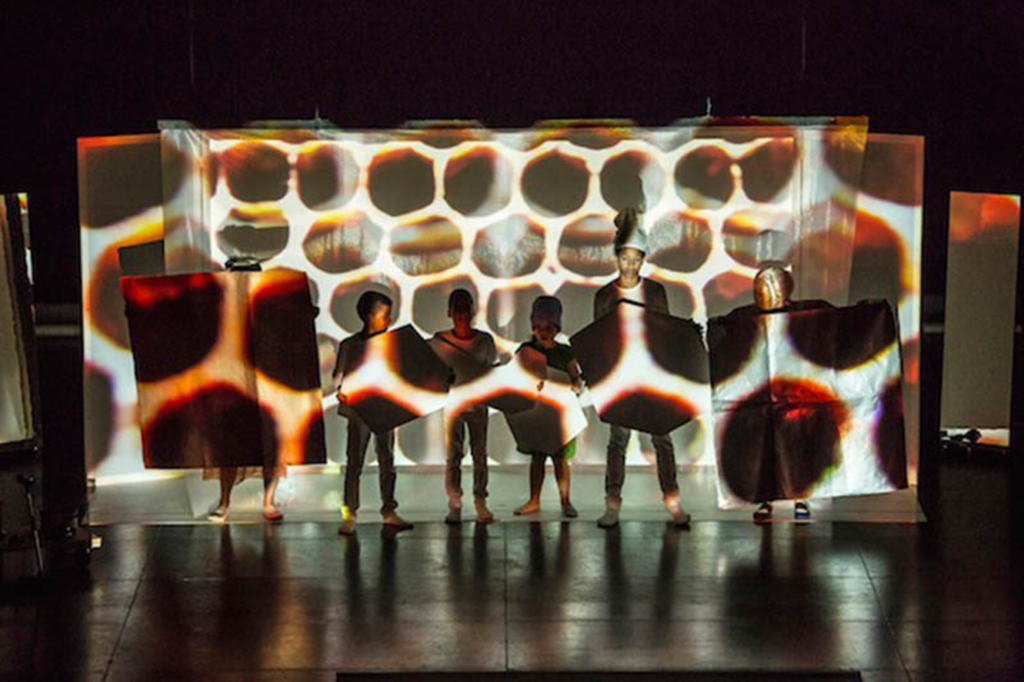

They Come to Us without a Word foregrounds memory, experience and time as it unfolds across five inter-related rooms through which ideas, images and stories move back and forth with the uncanny logic of a dream. In the first, Bee room, the central importance of symbolism in Joan’s work is clearly evident. The honeycomb, dancers, objects and drawings all evoke her early performance Organic Honey’s Visual Telepathy (1972), in which she performed as her female alter-ego Organic Honey alongside four other women, all wearing masks.

At one point in the performance, Joan put on all the masks worn by the other performers, as though attempting to integrate their various personae within a single mask, or self. As Joan herself observed, “Organic Honey was really about what it means to be female. I was exploring the idea of whether there is such a thing as female imagery. That was being discussed then in the late sixties and early seventies. For the character, Organic Honey, I was exploring an erotic persona through costume, gesture, and mask. I had gone to see Jack Smith, who had greatly affected me. He was so different from everything else that was going on at the time. He was much more baroque and that interested me a lot. It gave me inspiration. I wanted to break away from what was going on then in dance. There was an anti-literary stance. People didn’t want to deal with literature, but from the very beginning literature was important to me.”(iv)

This challenge to heteronormative models of the erotic and to the white male anti-literary norms of 1970s Postmodernism locates Joan’s work at the center of current debates. Ninety-five per cent of bees are female. When we look at the Bee room, with its reference to bees drawing nectar from dandelions to take back to the hive in what the Icelandic novelist Halldór Laxness, in his Under the Glacier (written the same year as Joan’s Organic Honey performance) calls a “super communion”, could it be that we looking at another symbolic collective female space: Organic Honey in insect form? In the current exploration of ideas of inter-species companionship, and a questioning of human exceptionalism, could it be that the duplication of Organic Honey’s image through mirrors, masks and performers in the 1972 performance is echoed here in the bees, rendered in ink drawings using the Rorschach technique of mirroring, situating Joan’s work at the heart of the new thinking taking place regarding gender, identity, and the Anthropocene?

Bees, and their anthropomorphic symbolism as bee-women, figure prominently in prehistoric Greek ritual and myth, as goddesses, supernatural beings, and symbols of female power. Two small gold plaques from the seventh century BC, each embossed with a winged Bee goddess, were recently found at Camiros in Rhodes. Priestesses worshipping Artemis and Demeter were called ‘bees’, and recent scholarship has revealed the strong possibility that women wore bee costumes in rituals and mummery during this period, and danced in clusters resembling a swarm.

The Bee room includes a drawing of a bee dance, including the round dance performed by the scout forager bee after she returns to the hive having found a new nectar source, to recruit more foragers to go and retrieve it. She flies over the honeycomb in close circles, alternating right and left, in patterns that evoke the way drawing often appears in Joan’s work: as a trace of dance-like movements describing a symbolic space. Near the diagram, a small glass bee made in Murano, Venice and a dead bee found there by Joan are displayed under magnifying glasses in small pools of light. Their lifeless forms evoke the sobering fact that seventy out of the top hundred food crops we rely on to survive — and which supply approximately ninety per cent of the world’s nutrition — are pollinated by bees, who are dying in large numbers from interrelated causes including pesticides, intensive agriculture, and climate change. The repetition of the bee in the Bee room takes on an apocalyptic tone, evoking Carlos Basualdo’s argument regarding Borges’s mirrored spaces, which “conspire to repeat for us our own image as a sign of absence and mortality.”(v)

A similar repetition appears in the Fish room, where drawings of Japanese fish hang in a gridded ocean of paper. In 2013 Joan made a hundred drawings of fish, inspired by a 1950s book Coloured Illustrations of the Fish of Japan by Toshiji Kamohara, for her exhibition at a residency at the Center for Contemporary Art in Kitakyushu. At the airport on her way to Kitakyushu, she experienced the Tohoku earthquake, whose subsequent tsunami caused a major nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Years later, radioactive water from the plant is still flowing into the Pacific Ocean at the rate of around 2 billion bequerels(vi) a day, reduced from 30 billion becquerels in 2013. The shoal of fish in these drawings, swimming in a ghostly suspended animation, marks a deeper engagement in her work with the natural world through its fragile ecosystems.

The dialogue between the internal world of myth, storytelling and symbolic space and the external natural world in Joan’s work has, since the beginning, been articulated through the presence of the body and its mediation by the mirror. As Bruce Ferguson has observed, Joan uses the mirror “not to reify the structuralist moment (where nature and culture…were interchanged in a systematic and masculinist manner [as in the work of Robert] Smithson. . .[Michael] Heizer [and others]. . .and where indices were transferred but never transformed) but instead, to examine its transitional spaces.”(vii) In other words, the mirror operates here as a tool for altering our perception of the space between the natural world and the self.

This in-between space is a subjective, psychologically charged space. In the Mirror room, it is articulated in a haptic, optical form by a group of large silvered panels leaning against the walls, whose cloudy surfaces soften our reflection, and that of the space, into an opaque image. The stark contrast between its dreamlike opacity and the sharpness of the two digital videos and a Venetian glass chandelier inside it, reverses conventions of how reality and fiction are optically understood, rendering impossible the notion of a single, fixed spatial reality.

This contrast between sharpness and opacity, stillness and movement, performative actions and objects, and between different registers of time is built through a complex process of layering. As Joan herself observed, “My idea of layering came when I began to work with different spaces of perception. For instance, by using a large mirror in a performance as a prop carried by the performer, one could see the real image of the performer simultaneously with reflections in the mirror moving in space. At the same time [that] I was doing my outdoor works in the landscape, I was working with perception of movement and forms in the distance and at different intervals from the audience. Then in my video performance, in which the audience saw simultaneously the live performance with a detail of that live performance projected, I began to think of juxtaposing different images and time sequences. These examples were obvious layerings in space.”(viii)

This process is rooted in the happenings and performances that occurred in the early 1960s in New York by artists such as Jim Dine, Carolee Schneemann and Claes Oldenburg, whose Storefront happenings involved the audience moving from room to room in a sequence that evokes the path of They Come to us Without a Word. Robert Whitman’s performance Prune Flat, first performed in 1965 at the Filmmakers Cinematheque, explicitly explored the relationship between the flat projected image and three-dimensional bodies and props, bleeding the space of each into the other. His co-founding of Experiments in Art and Technology grounded these experiments with layering and time in technology and cybernetics. Joan’s thinking engages more deeply with the intersection between cybernetics, human perception, biology, and ecology, in spatial models that evoke the arguments of psychologist James Gibson, whose 1979 book The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception explored the ways in which humans’ perception of their environment is expanded when their visual system is allowed to explore space from multiple layered surfaces, light levels, and viewpoints.

They Come to Us Without a Word folds these ideas into the most extensive engagement with the natural environment in Joan’s work to date. Like bees and fish, wind can be an indicator of a disrupted ecosystem. It has also operated in her work, since her first film, Wind, made in 1968, as a medium. In that film, the vastness of a snowy beach in Long Island, New York, became the stage for a group performance in which the performers, placed at various points in the near and far distance, attempted to map out space, moving against the considerable force of a strong wind. The fragility of the handmade paper kites hanging in the Wind room, the fourth room in the exhibition, underlines even more starkly the instability of the relationship between humans and the natural world.

The ghost stories from Cape Breton that thread through each room come together in the final room of the show, the Human or Homeroom, as storytellers become visible entities through their performative actions on screen and in their drawings hung on the walls. Storytelling appears throughout the exhibition not only as a connecting thread but also as another kind of mirror, multiplying the ways in which humans experience the world, layering spoken word with landscape, which Joan has always regarded as a form of narrative in which the elements become a character. The powerful volcanic landscape of Iceland appears frequently in her work, interwoven with elements from that country’s medieval and contemporary literature. In Under the Glacier, Laxness’ refusal of narrative logic echoes throughout Homeroom, recalling the character Pastor’s words as he explains unexplainable facts in a story to the Emissary: “History is always entirely different to what has happened… the closer you try to approach the facts through history, the deeper you sink into fiction. . . . The difference between a novelist and a historian is this: the former lies deliberately and for the fun of it, and the historian tells lies in his simplicity and imagines he is telling the truth. . . .“ To which the Emissary replies: “I set down, then, that all history, including the history of the world, is a fable.”(ix)

In an era defined by technological and political obfuscation, racial discrimination and violence, preparations for inter-galactic migration, and the irreversible crisis of climate change, Joan’s work has the quality of both a mirror held up to what is happening around us, and a potential model for new ways of thinking. The generative power of her approach can be seen in the work of a new generation of artists including Allison Janae Hamilton, whose video installation Floridaland (2017) addresses racial and ecological issues in the history of the South through storytelling, personal history, and myth. In the video, women in animal masks move through the forests, swamps and agricultural land of North Florida and Western Tennessee, a landscape dominated by the history of slavery, white power, exploitation, and hierarchies of race and class. The historical resistance of the communities, including Hamilton’s farming family (the women in the videos are the artist, her mother, and her godmother) appear in images evoking mystical references from Hoodoo — the knowledge of rural black healers — and the surrounding landscape. The sound of birds, insects, and percussion create an atmosphere of anxiety, not only about the land’s traumatic past but also about its future, through the looming consequences of climate change, and in particular hurricanes, which impact disproportionately high numbers of the black community in the South.

The urgency of the underlying issues present in Joan’s exhibition, and in her work’s dialogue with a younger generation, are magnified in her performance Moving off the Land, in which the ocean becomes the central subject. Deep sea footage filmed by Joan’s collaborator David Gruber, a marine biologist and environmental scientist specializing in the ecology of coral reefs and fluorescence, is projected onto the stage alongside footage of fish, an octopus, sea horses, and sea urchins, some by filmmaker Jean Painlevé, immersing the artist in the depths of the ocean. Wearing a wreath of seaweed and tiny glowing lights, and sometimes a mask, she alternately reads, draws, observes, and moves with the fish and other creatures swimming and gliding across the screen, their movements guiding hers, almost as though she is becoming one of them, echoing the trans-species communication that occurs throughout They Come to Us Without a Word.

The transition from the earth to the sea made explicit in the title of Moving off the Land evokes the ecological writings of marine biologist Rachel Carson, whose books Under the Sea-Wind (1941), The Sea Around Us (1951), and Silent Spring (1962) Joan read in the 1960s, at the beginning of her career, and recently re-read. “It is a curious situation”, Carson wrote, “that the sea, from which life first arose, should now be threatened by the activities of one form of that life. But the sea, though changed in a sinister way, will continue to exist; the threat is rather to life itself.”(x)

That Carson’s words should reappear in Joan’s thinking, forty years after they were written and read by the artist and countless others, underlines the acceleration of their urgency. Her warning evokes Shakespeare’s words from “Ariel’s Song” in The Tempest: “Full fathom five thy father lies/of his bones are coral made/those are pearls that were his eyes/nothing of him that doth fade/but doth suffer a sea-change/into something rich and strange.”(xi) This description of a return to the sea from whence we all came is a death song; yet the sea is also symbolic of the unconscious, and the maternal body. In Moving off the Land, the sea is teeming with intelligent life, suggesting that its fate and ours are inextricably linked. It is in the implications of this that we can, perhaps, learn how to prepare to live in the future.

Chrissie Iles

Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz Curator

Whitney Museum of American Art

Footnotes:

i ‘Joan Jonas’, Liam Gillick, interview with Joan Jonas, Art Review, March 2018

ii Jens Schröter, 3D: History, Theory and Aesthetics of the Transplane Image. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

iii Matthew Biro, The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2009, p. 3.

iv “Drawing My Way In: Joan Jonas in Conversation with Bonnie Marranca and Claire MacDonald”, Performing Arts Journal 107, Vol. 36, May 2014, pp.45-46

v Carlos Basualdo, “Life on the Mirror’s Edge.” Mirror’s Edge (exh. cat.), Bildmuseet, Umeå 1999, p. 33

vi A unit of radioactivity

vii “AmerefierycontemplationonthesagaofJoanJonas”, Bruce Ferguson, Joan Jonas, (exh. cat.), Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam 1993, p. 18.

viii “Drawing My Way In” op.cit., p.40.

ix Halldór Laxness, Under the Glacier, 2007, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, pp.78-79.

x Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us, Oxford University Press, 1951

xi William Shakespeare, “Ariel’s Song,” in The Tempest, Act I, Scene ii, 1610

The Art of Joan Jonas at Fort Mason tells of Ghosts and of Life

It matters, on her own terms as an artist and to us as her audience, that Joan Jonas is 82 years old. [SFChronicle]

Joan Jonas Endures With Her Strange and Entrancing Rituals

A profile of the artist before a banner year in 2018: pre-Tate Modern retrospective, pre-Kyoto Prize. [NYTimes]

New York Performances: Joan Jonas

A look back at Joan Jonas’ pioneering work in performance and video art. [Art21]

Q+A: Sofie Ramos

San Francisco-based artist Sofie Ramos creates fantastical installations that suggest a painting expanding into space, often engulfing the viewer, fluctuating between playful magic and underlying darkness. Frank Smigiel, Director of Arts Programming & Partnerships at FMCAC, sat down with Ramos for a conversation about her multifaceted work and creative trajectory.

Frank Smigiel (FS): Tell us a little bit about your background with traditional painting.

Sofie Ramos (SR): I studied painting at a university (as opposed to an art school), but there was this one class in undergrad which kind of changed my trajectory. It was a themed undergrad painting class called “Accessorising Painting” with the great Wendy Edwards at Brown. The idea was to connect painting to some other area of interest that would then transform the process or product of a traditional painting. I chose interior design, which I had also been getting into as a college student with a space of my own to decorate freely for the first time, my dorm room. I was always thinking about where paintings belonged or lived after you made them, and the idea of galleries and museums and all these institutional art spaces were not a huge part of my experience at the time. I thought of paintings as belonging in homes and as a possible element of interior decoration. I started arranging paintings along with other objects in my studio and thinking of the space around them and combining them with the space in different ways.

FS: Before that class, what would your paintings typically look like?

SR: I was really into this staining technique with liquid oil paint on raw canvas that would soak through to the back and then I would take the canvas off the stretcher, reverse it and reattach it to the stretcher, showing the back kind of accidental composition as the finished painting. I was clearly starting to get interested in a painting as an entire object and the materiality of the paint itself. I was only using oil paint because that’s what we were learning in painting class, so I will probably never go back to this technique again, though my friends in undergrad loved them and bought them all. Not sure how long those last, though. They are definitely not archival.

FS: And is it paint itself that’s really interesting to you as a material?

SR: Paint as material is very important; house paint in particular. I’m interested in how paint can transform objects, not necessarily in creating an image with paint, but bringing out a texture or combining surfaces and things like that. I think of it almost as kind of a sculptural material … also a way to clean things, to cover up histories and memories—this idea of repainting something over and over again to give it a fresh look or feel, a new face.

FS: It sounds like thinking about paint as an architect or a sculptor; not for the image it can make but for the kind of environment or field. I just think about those… how do I even describe them? What are those knobs that are on the fencing structure?

SR: They’re cotton balls dipped in latex house paint. I think of paint as a way to fossilize things; it’s not turning into rock but it is turning into plastic—latex paint is plastic. Especially soft materials will soak it up and turn it into something else entirely.

FS: You’re talking about the way paint at some level erases and makes a room brand new and at the same time that it fossilizes and holds a position that’s kind of back and forth. You see it all across your work: erasing, holding and accumulating.

SR: I don’t know that erasing happens so much but definitely covering up, which is another great thing about paint, the layers that existed before are still there so there is a tangible history that is built through all these layers.

FS: Talk about the everyday objects in the work.

SR: Well I’m really interested in these domestic objects or objects from the home as opposed to formal shapes. I don’t want to get lost in abstraction necessarily. I would like there to be some sort of familiarity in the objects and a connection to people; myself and the audience. So I try to use found objects as much as possible, though I usually alter them to some degree. I’ve collected many household objects—I love tables and chairs, I have a couch now, mattresses, blinds and lamps—and a lot of them will travel from installation to installation. Sometimes I refer to them as “imaginary friends” or as my cast of characters that come with me to whatever site I’m installing in and I build up the space around them.

But they also can do their own thing. I’m more of a facilitator sometimes than an all-knowing God figure that can place everything and know how everything goes. Sometimes I feel like the work makes itself and the objects evolve from space to space. They can interact with each other and the space in ways that can alter them and their surroundings.

With this project I’m getting more interested in story telling or at least developing my individual characters. I was getting into this with Chris [Wood] when we were trying to decide on the sounds, we were discussing that maybe the stairs and the pink ottoman are kind of fighting with each other because they are both a little bit aggressive in their sounds and maybe the breathing subwoofer coffee table is kind of the mother of everything, calming everything down but also getting angry with everyone, and then the tube scarf and the green ottoman are kind of consoling each other but also bickering a little bit. The collaboration between sound and performance are really key for introducing outside narratives into my spaces, which I think is becoming very important. I haven’t thought of that so much in the past because it’s kind of an alternative world, but what happens when something else comes in from the outside? Does it start to influence what’s going on in the space or change to the mood of the sculptures? I’m very interested in how these outside elements can start to interfere with and activate my spaces.

FS: Could you talk about the guardhouse? Do you start an installation with an “imaginary friend” and grow it out from the sculpture, or do you start with a series of marks and then find who’s going to fit into the environment? I mean there’s so many layers but you don’t seem to come with a set drawing.

SR: I sometimes try to make plans for an installation but I really prefer to be in the space and work improvisationally. I don’t necessarily start with all the objects, but a few of them have these paths attached to them, so paths have been emerging as a theme for a while now. The paths will mark out the space, or lead me and the objects through a space, but then also expand the space. So once there’s two or three paths going—usually attached to my stairs or a slide or a plank of wood and extended throughout the space—then I populate that part of the installation with more objects which will then also get painted into the space in some way and act to kind of dictate the composition through this process of meandering and building up.

FS: What you’re calling paths, the kind of very big lines in the work, I don’t think I’d realize that they were in many ways the generator. At some level you can think “oh they connect things that are already there” but they’re actually setting out the terrain.

SR: It’s kind of like a board game; setting out or creating some kind of parameter to go from.

FS: So does that mean that at least for right now, you wouldn’t think of these installations as things you repeat?

SR: I think people are aware that that’s not how it works, but at the same time I would definitely be interested in taking all of those elements to a different space and recreating a new installation out of them. Some of them are more connected to past installations than others. Everything changes in a different space so it’s always fun to see how something can translate or transform. I think that’s most of the process anyway—taking all the same stuff to a new site and seeing what happens.

FS: How much did the space change your way of working? The guardhouse is so unusual: it’s a small interior and people can only see it through the windows. Was this the first time you had to work with four walls, a contained space?

SR: It’s one of just a few times I’ve had four walls, although I wasn’t necessarily thinking of it that way because it still seems kind of, I hate the word “set”, but like a stage set because of the orientation of the windows. There is a front and there is a place where the audience is supposed to stand. It’s obviously a different experience when you walk inside. I am kind of sad that people can’t go inside because it’s more fun when the door is opened. And it’s fun to have the windows open too. If the windows are open, you can actually peek your head in.

FS: What did you learn from doing the big piece on the fence?

SR: I approached it kind of like I would in an empty room. I’ve painted a similar pattern to that on the walls before and the walls that I work on don’t always have a ceiling so sometimes I am able to put something like the line of triangles on top, so it’s a familiar composition but not on quite this big of a scale. That’s definitely the biggest thing I’ve ever made and I love it because it’s like an inversion of my spaces. I would love to play with that idea some more. I want to further connect it to the guardhouse and start populating it as a space; it is plywood and you can drill things into it. I don’t know if sculptures are allowed outside but I think it’s very interesting to have an inverted environment… I would love for it to keep evolving. I have also thought about the idea of streamers or something coming over the edges so it looks like something is inside, which everyone is always very curious about with this weird impenetrable structure.

FS: Younger kids are constantly looking for the door.

SR: Yeah, adults too. They’re like, “How do we get inside, what’s inside?” I’m like, “It’s an electric transformer.”

FS: One of the things about the fact that you can’t get inside either of them is that physical limit. You always have a built-in tension in the work. You work in a color palette that could be described as exuberant or fun, playful, but when you were talking about the guardhouse specifically, you are also talking about feelings of claustrophobia. One of the guys down in Goody cafe described the fencing as “the most menacing bouncy castle” he’d ever seen. So it’s not just a fun color wheel or with pathways, it’s got other darker or complicated or anxious edges to it.

SR: I am always trying to push it to be more complicated or complex, that’s definitely a goal.

FS: Do you set out to think you need to put something oppositional, scary and dangerous into it?

SR: I definitely love color and I want to make art that is fun, but at the same time I don’t want to get stuck in that superficial realm. I started amping up my color choices and really saturating my spaces towards the end of grad school, and the audience reaction to it became a little upsetting when it was just all about the fun, playful aspects, but then there were always people picking up on an underlying anxiety in the work. It can be very meticulous, and these straight lines that I’m making are kind of shaky and it’s not always fun to make it. It’s a little bit of a painful process sometimes and that has to do with being a perfectionist and all of these things that I’m trying to get away from. I talk a lot about the nearness and instability of formal and psychological oppositions, when oppositions co-exist at once or easily tip from one to the other; when it’s both super playful and kind of scary at the same time or pleasurable but also slightly nauseating.

FS: You don’t mind when people describe the work as an exploded painting?

SR: No, I love that. That’s how I always thought of it—as painting in space—and I think that’s how the whole practice was born but also it is also about the paint itself; I don’t know that it exploded exactly, but it started growing and expanding out of the frame, onto the space and then changing the space entirely.

FS: I read that one of your dream projects would be to have a whole house you could modulate.

SR: Yeah that’s still a dream, only to put it out there. Although I feel like the guardhouse was my first little house because it is its own structure, so I’ve been referring to it as my home. It’s a little too small with just one room but I would love that as a project.

FS: I love artists who make sculptures that they also use as a set or prop. I guess I wasn’t thinking about your work that way, and I was really surprised when you said the dancers were going to take the sculptures and move them out. You’re not afraid to let the sculptures kind of literally go out and then come back.

SR: Well this is a very new development, actually. I have previously had a lot of anxiety about anyone touching my shit and messing stuff up because it happens so much in my installations and galleries where people are like “I’m going to climb on these stairs” and then they break, or like “I’m going to sit on this spiky stool” or something. Obviously you’re not supposed to sit on that. I think it’s a really freeing experience to start thinking of sculptures as props. I would prefer them to be both. Because I’m constantly reusing them myself and repainting them, I have learned that they’re not so precious. You can always just paint over that scuff mark and then it’s gone and it’s like brand new.

FS: It was interesting in Rachael Cleveland’s piece [Moving In] and the way the performers were so focused on the sculptural objects that the movement kind of became object-like and became about those objects. It didn’t feel to me like those performers were just gratuitously using the objects, it felt very much controlled by the logic of the installation.

SR: They were very respectful of all the things. We had many conversations about it but they understood that the objects are characters on their own and treated them like that. The objects have personalities but also the people were becoming more like the objects and there was this weird hybrid interaction that was happening which I loved, so I think that I will continue to push the objects into these maybe more uncomfortable situations and see what they’re capable of.

FS: I wanted to talk about density. There are some pieces that have more air or more space and have a kind of central image and just one or two elements. Is it something that you increase over time, modulating back and forth between things that are more open, and things that are very knotted together?

SR: My work did grow in its layering and accumulation in my more formative years, especially in grad school where I pushed the saturation to its limits in my thesis project, which was a video called decorate/defecate. Now I feel like I can alternate pretty freely between more open and more dense fields depending on the context and the scope of the project. I think of the pieces you’re referring to as individual artworks as opposed to my installations, which are composed of many individual pieces, though the idea is that you can’t tell where any piece begins or ends. The major difference for me in my variable presentation methods is more of an autonomous work that maybe someone could own verses an environment where all of these things come together.

FS: What’s also interesting for me about the Fort Mason piece, particularly with the fence, is just how much it’s influencing the campus. It’s extending its own kind of gravitational pull. It’s interesting to see it not contained in a gallery space but out in the world.

SR: Yeah, I’m definitely into the work out in the world. I will obviously always return to the comfort of the interior setting, but galleries are really not ideal anyway. I think next I need to make an entire structure, where both outside and inside are integrated into a total work of art. I guess it’s similar to moving beyond the confines of the painting frame, to move outside the walls of the space.

FS: I know you have qualms about art work that’s interactive but I think you mentioned somewhere that you’d love to do a playground.

SR: Yes, I’m down for the playground project if I can work with some people to make it sturdy enough to play on. But more interesting than a playground for kids would be one for adults that’s like an obstacle course or a death trap, it would be fun if there could be more than just the play aspect to it. Things that could fall on you or a big pool of painted cotton balls … yeah, I would hope that in the future projects can expand to be on that scale.

Sofie Ramos Makes Mischief

Sofie Ramos makes endless installations that are immersive, decidedly mischievous and always site-specific. [JUXTAPOZ]

Withering Critiques of Capitalism in “Isaac Julien: Playtime”

Since it appears we’re truly, seriously headed for a new Gilded Age courtesy of the GOP’s tax scam, it feels perversely appropriate that Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture (FMCAC) is the new home of a mostly cinematic exhibit by a poetically damning British artist and filmmaker. [SF Weekly]

Isaac Julien’s ‘Playtime’ Is an Econ Lesson Disguised as Cinema

What drives people to cross continents and borders in search of a better life? What does something look like when it can’t be pictured? Watch, or rather, walk through these and other questions posed by way of three major works by British video and installation artist Isaac Julien, on view at the Fort Mason Center for Arts and Culture and opening December 1. [San Francisco Magazine]

It’s ‘Playtime’ at Fort Mason and there’s video

For those of us who were around to see the first video works presented in art museum and gallery exhibitions, our memories are in grainy black and white. [SF Chronicle]

Sophie Calle at Fort Mason: Reports from love’s front lines

The French artist Sophie Calle — I accept that she is an artist, though “visual author” may be more apt — will make you cry.

Sophie Calle: ‘What attracts me is absence, missing, death…’

She makes art that is intimate, romantic, funny, dramatic and confessional… And yet after four decades there are still new truths about Sophie Calle’s past to be revealed.

Sophie Calle Exhibit at Fort Mason Gives ‘Good Grief’ a New Meaning

Missing, on display through August 20, presents four of the French conceptual artist’s most celebrated works.

The Fertile Mind of Sophie Calle

France’s most famous conceptual artist might finally be getting the attention she deserves — in America.

Equator Coffee headed to Fort Mason

Equator Coffees & Teas has plans to open its third San Francisco outpost sometime this summer at the Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture.

Photography festival coming to San Francisco

On the heels of the landmark re-opening of SFMOMA and the inauguration of the Minnesota Street Project, the robust photography community in the Bay Area has long lamented the lack of a festival to match their fervor. PHOTOFAIRS | San Francisco hopes to change that.

A Preview of the Fog Design + Art Fair in San Francisco

Five years ago, Stanlee Gatti realized one of his dreams. The event planner extraordinaire had always hoped that San Francisco would have its very own contemporary design fair.

Fog Fair celebration of art, design clearly a success

Four years ago, when Fog Fair first blew into San Francisco, its ambitions were at once focused and relatively modest.

These Photos Capture the Bleak Beauty of Wildlife in Captivity

Scenes from the concrete jungle, by photographer Eric Pillot.

Reflecting on Art: The Eight Best Things I Saw in 2015

Janet Cardiff’s sound piece might be the most recommended Bay Area art experience of the year — and not just by me.