Chrissie Iles on They Come to Us without a Word

Chrissie Iles, the Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, spoke about pioneering American artist Joan Jonas and the arc of her work on the occasion of the U.S. premiere of Jonas’ commission for the 2015 Venice Biennale, “They Come to Us without a Word.”

To experience the work of Joan Jonas is to enter a labyrinthine imaginative space, whose complex structure of meaning is rooted in an encyclopaedic context encompassing literature, ancient myth, land art and sculptural issues of non-site, dance, theatre, performance, ecosystems and identity. This wide-ranging context describes the condition of seventies Postminimalism out of which Joan emerged, and whose hybridic, process-based character her work played a major role in defining.

Each of Joan’s works encompasses elements of drawing, performance, installation, sculpture, video, sound, objects, and storytelling that all co-exist in relation to each other, spatially, conceptually, and also across time: elements from one work frequently appear in another, sometimes forty years later. The artist Liam Gillick described the central importance of performance in this approach in a recent interview — “[Y]ou are editing in real time…chopping and cutting, breaking and interrupting.” — to which Joan replied: “ [I am] interested in revealing the process…. I am showing you how I make it… [It’s] related to Surrealism and juxtaposing disparate ideas, objects and images.”(i)

The narrative structure of Joan’s work also evokes the literary influence of Magic Realism, in which the real and the present mix fluidly with the fantastical and the surreal. In They Came to Us Without a Word, we are taken through five rooms, each of which has two videos: one addressing the main motif of the room, the other a fragment of a second, ghost narrative that runs through all the spaces, picking up from the previous room and taking us forward into the next.

Layered onto this double narrative is an immersive collage of drawings, objects, sculptural forms and mirrored surfaces in arrangements that resist easy definition. We are not looking at the traces of a performance that has happened, even though a performance has taken place in parallel to this work, and props, objects, and video footage from that performance are present. And we are not looking at a stage set, nor an installation in the conventional sense of the term, even though the structure of each room resembles both. The space is, to use Jens Schröter’s term, transplanar (ii): a multi-planar surface that opens up the optical border between two and three-dimensional space, creating an environment that can become a portal into new readings of narrative, space, identity, and time.

This haptic structure was first formed by Joan in the cybernetic environment that emerged in the 1960s, and it is one of the many reasons why Joan’s work remains so resonant now, in the deep interconnectedness of our all-surrounding digital environment. As Matthew Biro observed of that period, “To view human beings as cybernetic systems was… to recognize their collaborative nature…subject to constant dispersal, transformation, and exchange.”(iii)

It is important to understand this, in order to put into context the central importance of myth, symbols, ancient ritual, and literature in Joan’s work. It has a feminist, cybernetic aspect that underpins her interest in writers and thinkers such as Aby Warburg and his “denkraum” (“space of thinking”), the labyrinthine spaces of Jorge Luis Borges, or the writings of George Kubler, whose book The Shape of Time pointed out that we understand history through its material traces, since temporal expression – talking, dance, song, music, ritual – have not, by their very nature, survived, except in the re-telling. Joan juxtaposes the material and the temporal in ways that profoundly understand this conundrum, and the importance of experience, memory, and what cannot be recorded or recalled, in the construction of meaning.

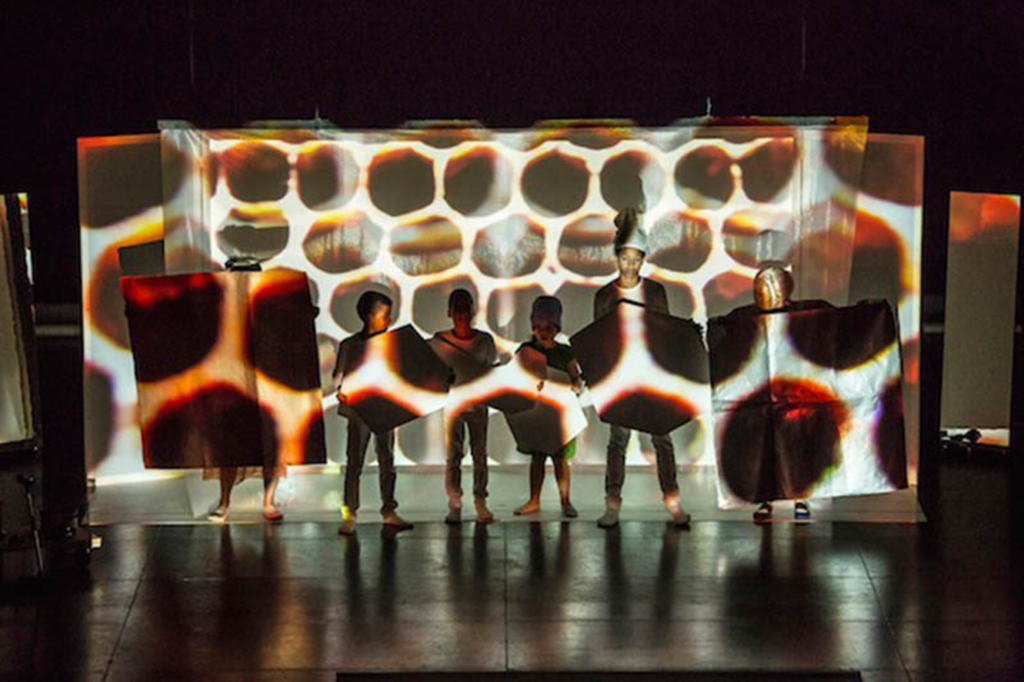

They Come to Us without a Word foregrounds memory, experience and time as it unfolds across five inter-related rooms through which ideas, images and stories move back and forth with the uncanny logic of a dream. In the first, Bee room, the central importance of symbolism in Joan’s work is clearly evident. The honeycomb, dancers, objects and drawings all evoke her early performance Organic Honey’s Visual Telepathy (1972), in which she performed as her female alter-ego Organic Honey alongside four other women, all wearing masks.

At one point in the performance, Joan put on all the masks worn by the other performers, as though attempting to integrate their various personae within a single mask, or self. As Joan herself observed, “Organic Honey was really about what it means to be female. I was exploring the idea of whether there is such a thing as female imagery. That was being discussed then in the late sixties and early seventies. For the character, Organic Honey, I was exploring an erotic persona through costume, gesture, and mask. I had gone to see Jack Smith, who had greatly affected me. He was so different from everything else that was going on at the time. He was much more baroque and that interested me a lot. It gave me inspiration. I wanted to break away from what was going on then in dance. There was an anti-literary stance. People didn’t want to deal with literature, but from the very beginning literature was important to me.”(iv)

This challenge to heteronormative models of the erotic and to the white male anti-literary norms of 1970s Postmodernism locates Joan’s work at the center of current debates. Ninety-five per cent of bees are female. When we look at the Bee room, with its reference to bees drawing nectar from dandelions to take back to the hive in what the Icelandic novelist Halldór Laxness, in his Under the Glacier (written the same year as Joan’s Organic Honey performance) calls a “super communion”, could it be that we looking at another symbolic collective female space: Organic Honey in insect form? In the current exploration of ideas of inter-species companionship, and a questioning of human exceptionalism, could it be that the duplication of Organic Honey’s image through mirrors, masks and performers in the 1972 performance is echoed here in the bees, rendered in ink drawings using the Rorschach technique of mirroring, situating Joan’s work at the heart of the new thinking taking place regarding gender, identity, and the Anthropocene?

Bees, and their anthropomorphic symbolism as bee-women, figure prominently in prehistoric Greek ritual and myth, as goddesses, supernatural beings, and symbols of female power. Two small gold plaques from the seventh century BC, each embossed with a winged Bee goddess, were recently found at Camiros in Rhodes. Priestesses worshipping Artemis and Demeter were called ‘bees’, and recent scholarship has revealed the strong possibility that women wore bee costumes in rituals and mummery during this period, and danced in clusters resembling a swarm.

The Bee room includes a drawing of a bee dance, including the round dance performed by the scout forager bee after she returns to the hive having found a new nectar source, to recruit more foragers to go and retrieve it. She flies over the honeycomb in close circles, alternating right and left, in patterns that evoke the way drawing often appears in Joan’s work: as a trace of dance-like movements describing a symbolic space. Near the diagram, a small glass bee made in Murano, Venice and a dead bee found there by Joan are displayed under magnifying glasses in small pools of light. Their lifeless forms evoke the sobering fact that seventy out of the top hundred food crops we rely on to survive — and which supply approximately ninety per cent of the world’s nutrition — are pollinated by bees, who are dying in large numbers from interrelated causes including pesticides, intensive agriculture, and climate change. The repetition of the bee in the Bee room takes on an apocalyptic tone, evoking Carlos Basualdo’s argument regarding Borges’s mirrored spaces, which “conspire to repeat for us our own image as a sign of absence and mortality.”(v)

A similar repetition appears in the Fish room, where drawings of Japanese fish hang in a gridded ocean of paper. In 2013 Joan made a hundred drawings of fish, inspired by a 1950s book Coloured Illustrations of the Fish of Japan by Toshiji Kamohara, for her exhibition at a residency at the Center for Contemporary Art in Kitakyushu. At the airport on her way to Kitakyushu, she experienced the Tohoku earthquake, whose subsequent tsunami caused a major nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Years later, radioactive water from the plant is still flowing into the Pacific Ocean at the rate of around 2 billion bequerels(vi) a day, reduced from 30 billion becquerels in 2013. The shoal of fish in these drawings, swimming in a ghostly suspended animation, marks a deeper engagement in her work with the natural world through its fragile ecosystems.

The dialogue between the internal world of myth, storytelling and symbolic space and the external natural world in Joan’s work has, since the beginning, been articulated through the presence of the body and its mediation by the mirror. As Bruce Ferguson has observed, Joan uses the mirror “not to reify the structuralist moment (where nature and culture…were interchanged in a systematic and masculinist manner [as in the work of Robert] Smithson. . .[Michael] Heizer [and others]. . .and where indices were transferred but never transformed) but instead, to examine its transitional spaces.”(vii) In other words, the mirror operates here as a tool for altering our perception of the space between the natural world and the self.

This in-between space is a subjective, psychologically charged space. In the Mirror room, it is articulated in a haptic, optical form by a group of large silvered panels leaning against the walls, whose cloudy surfaces soften our reflection, and that of the space, into an opaque image. The stark contrast between its dreamlike opacity and the sharpness of the two digital videos and a Venetian glass chandelier inside it, reverses conventions of how reality and fiction are optically understood, rendering impossible the notion of a single, fixed spatial reality.

This contrast between sharpness and opacity, stillness and movement, performative actions and objects, and between different registers of time is built through a complex process of layering. As Joan herself observed, “My idea of layering came when I began to work with different spaces of perception. For instance, by using a large mirror in a performance as a prop carried by the performer, one could see the real image of the performer simultaneously with reflections in the mirror moving in space. At the same time [that] I was doing my outdoor works in the landscape, I was working with perception of movement and forms in the distance and at different intervals from the audience. Then in my video performance, in which the audience saw simultaneously the live performance with a detail of that live performance projected, I began to think of juxtaposing different images and time sequences. These examples were obvious layerings in space.”(viii)

This process is rooted in the happenings and performances that occurred in the early 1960s in New York by artists such as Jim Dine, Carolee Schneemann and Claes Oldenburg, whose Storefront happenings involved the audience moving from room to room in a sequence that evokes the path of They Come to us Without a Word. Robert Whitman’s performance Prune Flat, first performed in 1965 at the Filmmakers Cinematheque, explicitly explored the relationship between the flat projected image and three-dimensional bodies and props, bleeding the space of each into the other. His co-founding of Experiments in Art and Technology grounded these experiments with layering and time in technology and cybernetics. Joan’s thinking engages more deeply with the intersection between cybernetics, human perception, biology, and ecology, in spatial models that evoke the arguments of psychologist James Gibson, whose 1979 book The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception explored the ways in which humans’ perception of their environment is expanded when their visual system is allowed to explore space from multiple layered surfaces, light levels, and viewpoints.

They Come to Us Without a Word folds these ideas into the most extensive engagement with the natural environment in Joan’s work to date. Like bees and fish, wind can be an indicator of a disrupted ecosystem. It has also operated in her work, since her first film, Wind, made in 1968, as a medium. In that film, the vastness of a snowy beach in Long Island, New York, became the stage for a group performance in which the performers, placed at various points in the near and far distance, attempted to map out space, moving against the considerable force of a strong wind. The fragility of the handmade paper kites hanging in the Wind room, the fourth room in the exhibition, underlines even more starkly the instability of the relationship between humans and the natural world.

The ghost stories from Cape Breton that thread through each room come together in the final room of the show, the Human or Homeroom, as storytellers become visible entities through their performative actions on screen and in their drawings hung on the walls. Storytelling appears throughout the exhibition not only as a connecting thread but also as another kind of mirror, multiplying the ways in which humans experience the world, layering spoken word with landscape, which Joan has always regarded as a form of narrative in which the elements become a character. The powerful volcanic landscape of Iceland appears frequently in her work, interwoven with elements from that country’s medieval and contemporary literature. In Under the Glacier, Laxness’ refusal of narrative logic echoes throughout Homeroom, recalling the character Pastor’s words as he explains unexplainable facts in a story to the Emissary: “History is always entirely different to what has happened… the closer you try to approach the facts through history, the deeper you sink into fiction. . . . The difference between a novelist and a historian is this: the former lies deliberately and for the fun of it, and the historian tells lies in his simplicity and imagines he is telling the truth. . . .“ To which the Emissary replies: “I set down, then, that all history, including the history of the world, is a fable.”(ix)

In an era defined by technological and political obfuscation, racial discrimination and violence, preparations for inter-galactic migration, and the irreversible crisis of climate change, Joan’s work has the quality of both a mirror held up to what is happening around us, and a potential model for new ways of thinking. The generative power of her approach can be seen in the work of a new generation of artists including Allison Janae Hamilton, whose video installation Floridaland (2017) addresses racial and ecological issues in the history of the South through storytelling, personal history, and myth. In the video, women in animal masks move through the forests, swamps and agricultural land of North Florida and Western Tennessee, a landscape dominated by the history of slavery, white power, exploitation, and hierarchies of race and class. The historical resistance of the communities, including Hamilton’s farming family (the women in the videos are the artist, her mother, and her godmother) appear in images evoking mystical references from Hoodoo — the knowledge of rural black healers — and the surrounding landscape. The sound of birds, insects, and percussion create an atmosphere of anxiety, not only about the land’s traumatic past but also about its future, through the looming consequences of climate change, and in particular hurricanes, which impact disproportionately high numbers of the black community in the South.

The urgency of the underlying issues present in Joan’s exhibition, and in her work’s dialogue with a younger generation, are magnified in her performance Moving off the Land, in which the ocean becomes the central subject. Deep sea footage filmed by Joan’s collaborator David Gruber, a marine biologist and environmental scientist specializing in the ecology of coral reefs and fluorescence, is projected onto the stage alongside footage of fish, an octopus, sea horses, and sea urchins, some by filmmaker Jean Painlevé, immersing the artist in the depths of the ocean. Wearing a wreath of seaweed and tiny glowing lights, and sometimes a mask, she alternately reads, draws, observes, and moves with the fish and other creatures swimming and gliding across the screen, their movements guiding hers, almost as though she is becoming one of them, echoing the trans-species communication that occurs throughout They Come to Us Without a Word.

The transition from the earth to the sea made explicit in the title of Moving off the Land evokes the ecological writings of marine biologist Rachel Carson, whose books Under the Sea-Wind (1941), The Sea Around Us (1951), and Silent Spring (1962) Joan read in the 1960s, at the beginning of her career, and recently re-read. “It is a curious situation”, Carson wrote, “that the sea, from which life first arose, should now be threatened by the activities of one form of that life. But the sea, though changed in a sinister way, will continue to exist; the threat is rather to life itself.”(x)

That Carson’s words should reappear in Joan’s thinking, forty years after they were written and read by the artist and countless others, underlines the acceleration of their urgency. Her warning evokes Shakespeare’s words from “Ariel’s Song” in The Tempest: “Full fathom five thy father lies/of his bones are coral made/those are pearls that were his eyes/nothing of him that doth fade/but doth suffer a sea-change/into something rich and strange.”(xi) This description of a return to the sea from whence we all came is a death song; yet the sea is also symbolic of the unconscious, and the maternal body. In Moving off the Land, the sea is teeming with intelligent life, suggesting that its fate and ours are inextricably linked. It is in the implications of this that we can, perhaps, learn how to prepare to live in the future.

Chrissie Iles

Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz Curator

Whitney Museum of American Art

Footnotes:

i ‘Joan Jonas’, Liam Gillick, interview with Joan Jonas, Art Review, March 2018

ii Jens Schröter, 3D: History, Theory and Aesthetics of the Transplane Image. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

iii Matthew Biro, The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2009, p. 3.

iv “Drawing My Way In: Joan Jonas in Conversation with Bonnie Marranca and Claire MacDonald”, Performing Arts Journal 107, Vol. 36, May 2014, pp.45-46

v Carlos Basualdo, “Life on the Mirror’s Edge.” Mirror’s Edge (exh. cat.), Bildmuseet, Umeå 1999, p. 33

vi A unit of radioactivity

vii “AmerefierycontemplationonthesagaofJoanJonas”, Bruce Ferguson, Joan Jonas, (exh. cat.), Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam 1993, p. 18.

viii “Drawing My Way In” op.cit., p.40.

ix Halldór Laxness, Under the Glacier, 2007, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, pp.78-79.

x Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us, Oxford University Press, 1951

xi William Shakespeare, “Ariel’s Song,” in The Tempest, Act I, Scene ii, 1610